Man from Snowy River Museum

This was the official website for the Man from Snowy River Museum. Content is from the site's archived pages.

103 Hanson Street

Corryong, VIC

0260761114

Yelp Reviews

***** Robyn C

Melbourne, Australia

Throw back in time.

We enjoyed our visit to the museum reminiscing about many things we saw reminding us of our grandparents and parents generation. Also worried us both that we recognised so much! Are we really that old! Well worth a visit when in Corryong.

Thank Robyn C

***** granite2014

Amazing collection of Snowy River History

This museum is a must see if interested in the history of the Snowy RiIver Region. The rug knitted by Jack Simpson whilst a WW2 POW is a feature of the museum. Make sure that you see the outdoor exhibits.

Thank granite2014

***** justmeok006

Melbourne

Amazing collection!

This is a fascinating place and you must stop in for a visit when you are in Corryong! Not only does it have the history of the Man from Snowy River it also has on display the hand knitted rug by Jim Simpson. This was knitted during WW2 whilst he was a prisoner of war. Hearing that his knitted jumper would be confiscated when he arrived at the POW camp he unravelled the jumper so it wouldn't keep the enemy warm! This rug is approx 2 metres square and was knitted using dixie can handles that were fashioned into knitting needles. The rug depicts the map of Australia with all states marked and the coat of arms of each state appearing above along with the rivers mountains and lakes! The knitting itself is superb and considering the implements used to produce it truly an amazing feat. Jim also taught other POWs to knit socks to keep their feet warm. Also on display is the dressing gown that Jim knitted on the ship on the way home to Australia. Another truly amazing piece. The rest of the museum is a collection of anything and everything! You could easily spend an entire day here! Out the back in the yard is the original schoolhouse and police station that were re-located here. Allow yourself plenty of time to visit this fascinating place to do it the justice it deserves. And my wife wants to add, the restrooms are clean and tidy, the toilet paper soft, and the paper hand towels easy to use. She was impressed with the woman who was cleaning the ladies room, wiping everything down with disposable Clorox disinfecting wipes. My wife works in a day car center and is familiar with the different types of disinfecting wet wipes that are available. The ones used in the museum's rest room was a clorox bleach-free, premoistened wipe that cleans and disinfects in one step, killing 99.9% of bacteria, including staph and salmonella. My wife sounded like a TV commercial telling me about them. I guess the bottom line is that the restrooms kept clean! Nice to know, particularly if you have kids.

***** oldbarbogans

Old Bar, Australia

Wow they have kept everything

what an interesting place to visit. The locals have definitely kept a lot of stuff to make their museum interesting. We went there to learn about the Man from Snowy River but left with a broad knowledge of the whole area. Lovely staff who are very friendly and passionate about their museum

The Man from Snowy River Museum is located in the foothills of the Snowy Mountains and the pure end of the Murray River in the picturesque township of Corryong.

Corryong is located in north east Victoria and has a population of approximately 1300 people. It has a broad range of accommodation to choose from including motels, caravan parks, free camping, bed and breakfasts and a 4 star resort at nearby Walwa.

No matter which direction you travel from, the drive to Corryong only becomes more beautiful as you approach the destination. Be sure to bring your camera.

| Melbourne to Corryong | 395km | 4 hrs 30 minutes |

| Wangaratta to Corryong | 190km | 2 hours 40 minutes |

| Albury-Wodonga to Corryong | 125km | 1 hour 30 minutes |

The pioneering families of the Upper Murray had a vision in the early 1960s to preserve the early Australian history of the Corryong region.

Today the commitment of the local communities to carry on the traditions and stories of early settlement through to the post-war years is an experience to behold. The organized clutter and unique display is loved by thousands of visitors each year who visit Corryong's Man from Snowy River Museum and Riley's Village.

People from all over the world visit the Museum to retrace their heritage as many early European settlers called the Snowy Mountains area home.

The Man from Snowy River Museum and Riley's Village tells the story of Jack Riley who was without doubt, the real man from Snowy River who inspired Banjo Paterson's famous poetry. This epic tale has an endearing place in the hearts of all Australians and is celebrated every year in Corryong at the Man from Snowy River Festival.

+++

The Legend of Jack Riley

It's true what they say, Banjo Paterson did meet the Man from Snowy River, Jack Riley, all those years ago.

Jack was the legendary horseman who migrated from Ireland to Australia as a 13-year-old in 1851.

Jack worked as a tailor near Omeo but found his true passion as a stockman, he worked for the Pierce family of Greg Greg, near Corryong.

Jack lived in isolation in a hut high up in the hills at Tom Groggin. He loved the Snowy Mountain Country, a good yarn and enjoyed a social drink or two. Jack was also a good mate of the late Walter Mitchell of Towong Station, who introduced Jack Riley to Banjo Paterson when the pair was on a camping trip. They trekked the Kosciusko Ranges and the Snowys, shared many campfires and yarns too. Jack Riley was the Man from Snowy River who provided an inspirational journey and material for banjo to write his now famous poem.

Banjo Paterson also wrote a poem about Jack Riley's cow. This is further testimony to a meeting with Jack and the friendship they shared.

Corryong was the closest township to Riley and the locals remember he would visit three or four times a year for supplies. When friends found him very sick and attempted to get him to a doctor it was Corryong Hospital they brought him, although he died along the way.

Jack Riley was buried at the Corryong cemetery in 1914 however, Jack's spirit comes alive every year in Corryong at the Man from Snowy River Bush Festival. The festival is a celebration of the famous poem, bush folklore, the arts, music and Australia's finest horsemanship.

Jack Riley's final resting place in the Corryong Cemetery.

+++

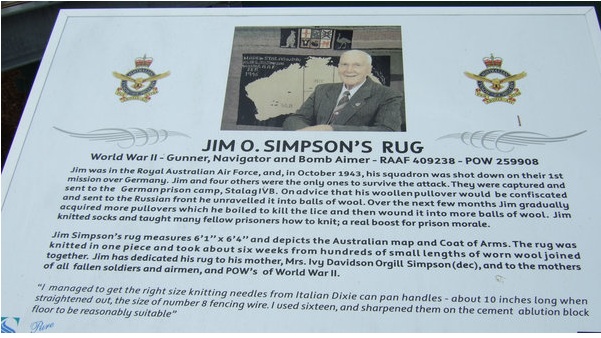

My Rug

Mr. Jim O. Simpson in 2006

This is a brief account of a long story regarding the knitting of a rug I made, mainly of used wool, in a prison of war camp in Germany, during the Second World War (1939-45). This rug was knitted in Stalag IVB Mühlberg on Elbe, Saxony, Germany.

I arrived in Germany on the 9th of October 1943, landing near Hannover at two minutes to two in the morning. I was a trifle upset because the C.O of our squadron was flying the Lancaster, and was supposed to be showing our 'Rookie' crew on their maiden sortie what to do. This flight to Hannover was his 40th mission; God only knows where he flew the other thirty nine sorties, for his example was so insidious, it showed with devastation what not to do. The result was we were shot down by a night fighter at a range of half a mile or so, at the height of 21,800 feet. Five of the crew died, three parachuted to terra firma safely, becoming uninvited guests of Hitler.

During transport to prison with many others, especially some Yanks, who informed me that I would lose my large white rolled neck naval pullover, as the "Jerries" were confiscating most warm garments to send to the Russian front. So first opportunity I dismantled it, ready to be unravelled and rolled into balls of wool, and it worked. I later bought another white naval pullover for fifty cigarettes, which were the currency of the 'Camp.'

After some months in the prison I realised it was almost impossible to escape to the west, being situated so far in the heart of Germany and not knowing the language, which was a must.

At about this time I had gathered quite a few worn out pullovers, some lousy, some not. Boiling the garments for a few minutes kills the lice and their eggs, and it did not seem to hurt the wool very much. I knitted a few pairs of socks for some who were eager to escape, but they all seemed to return rather crestfallen, but; with socks intact. With this result I gathered enough wool, so I started teaching some of the lads to knit, about forty in all. They were really good lads, especially the R.A.F. boys. They were helpful in getting more old worn out pullovers to delouse, dismantle and roll into balls of wool of many colours. I had Red Cross Parcel boxes of balls of wool, especially the white wool, which was to be used in the White Map of Australia, which I had envisaged to be able to produce for the centre piece of my rug. The Jerries were very curious about these boxes of wool, but accepted my explanation for them.

After nearly twelve months in prison I started to plan the design and details of how to use the knitting needles as pencils to draw the map and its surroundings. The map I drew was a bit faulty, with the positions of the islands in Bass Strait, and the other mistake was made with the Barrier Reef. I had drawn the original map with the Barrier Reef to the Thursday Island, but when I knitted to about Cairns, somebody turned up with a Red Cross book map of Australia, which put the Barrier Reef finishing opposite Cairns. I was reluctant to accept this as being correct, but as I was in a minority, I was told I was too obstinate, especially not with a college education, I unwisely relented.

Noting that I was educated in the bush, and as it so happened in my youth I had painted the Australian Coat of Arms many times for friends, and I knew it to be correct, so to take a rise out of these College graduates I asked them to draw me the Australian Coat of Arms. It amazed me to find that out of thirteen Aussies, not one had it right. Really pathetic!

The red wool for the Coat of Arms was from a new pair of Canadian Hockey socks, and I knitted another pair of ordinary socks for the good hearted Canadian. I managed to get the right sized knitting needles from the handles of Italian Dixie can pan handles, about 10 inches long when straightened out, the size of number 8 fencing wire. I used sixteen, and sharpened them on the cement ablution block floor to be reasonably suitable.

The rug itself was knitted in one piece, the Coat of Arms and all. The Crown Jewels were worked with a needle and coloured wool, five crowns for the Cross of St George for NSW's, one crown for Victoria's Southern Cross, and one crown in the centre of the Maltese cross for QLD.

The knitting time to make this rug was about six weeks. The winding of the wool, some well worn, some reasonable, to make it twelve ply, took many months to get a reasonable article to knit with. There were hundreds of small sections or worn wool joined together to be reasonably even. I had no trouble with the Germans in making this article, as a matter of fact they were rather astonished with the finished product.

After being released by the Russians, conditions for food and welfare became chaotic. I was absent foraging for food when our Compound marched out to Riesa, and only for my good friend, Rudd Penny from Brisbane, I would have lost my ring. He knew I was out, so he collected the rug, bag of all sorts, and left word with the English Tommies what he had done. I was very grateful for this act of goodwill, which was so prominent amongst our boys.

After returning to the Stalag IV from the foraging exercise, my mate, a New Zealander and I, made haste and caught up with the rear units of our compound, and I was able to collect the rug and bag of all sorts from Rudd.

I only stayed the night at Riesa; for the Russians began fencing in our barracks to stop escaping, and at that time, one of our boys' acquired wireless, 'Winnie' was yapping about the Polish question of occupation by the Russians. We were a bit worried that we could end up pulling barges at the Volga. Word was around on the grapevine that the British were going to pay eight shillings per head for allied prisoners to the Russians. It was quite apparent we had to fend for ourselves, so we left Riesa very early next morning on our push bikes, which we had salvaged from a scrap the 'Ruskies' had with SS troopers on a lonely road through a forest, which crossed our path while returning to the old Stalag IVB the day before. My 'Kiwi' mate, named Jim Buckham from South Island, New Zealand, was a little older than myself, well built and strong, very essential for survival in this sort of existence.

A few miles out of Riesa we ran into about a dozen Russians, ten of them laying down drunk, apparently on wine which came from a place where they made vinegar out of it. Two of their members were not drunk, and when they seized our bikes, we had to take rather immediate drastic action. Jim knew what to do with his fellow, quietly was the order of the operation. They were all over armed, and if they started shooting, it would bring more of their mates. I strangled my fellow until he collapsed and went quite limp. He had three lugers in his belt, too many, and I made sure his hands could not reach them.

We tossed each Ruskie down the bank of the autobahn, hopped on our bikes and rode flat out. We had only gone about two hundred yards, and to our surprise, they recovered enough to start shooting in our direction. We needed no further encouragement to make full speed ahead.

We rode to the Mulde River, the boundary of the Russian and Yankie sectors. There the American on duty with a Russian would not let us cross the narrow swinging foot bridge, we were totally rejected by the American classing us as refugees. There were hundreds of displaced people waiting closer by to cross the bridge. Other large bridges had been destroyed during the German retreat, so temporarily this little foot bridge was the only way to cross this deep little river about fifty yards wide. Anyone who tried to swim the river, were fired on while trying to do so.

The Russian, with the American on duty, recognised us, as he had come out of Stalag IV and showed thanks for the food we had given him some months before, by indicating to the Yank to let us over. Once in the American Section, everybody seemed quite happy. We managed to get a ride from near where we crossed the Mulde River to Leipzig, some fifteen miles, in an American Army truck. They treated us very well by taking us to their mess to have dinner. They were astonished when we picked up white bread and ate it as cake. We had never tasted better bread, for we had been used to "Jerrie" bread which consisted of 40% wood pulp, 30% of potatoes and 30% rye flour.

After dinner we managed to have an interview with the Commanding Officer of the American department for the repatriation of Allied prisoners. We were told they would give us clothes, etc and take our bikes and my bag of junk, then fly us from Halle to Reims in France, where the British would take charge. I told this Officer I could not let them take my bag, because I had some cherished mementos in it; so we had better get on our bikes and ride to the English Channel coast, then get a boat and cross the channel to 'Pommie Land.'

"Before you do what you say, let me see what is in the bag," he said. We pulled out the wire needles, then the rug, and spread it on the clean floor of his office. He looked, questioned and said "it seems to be made in one piece, I wish my wife was here." Jokingly I said, "you must hate to have to bring her to this place." He said she was a keen knitter and had never "seen anything like this. You can keep your bag of mementos intact and don't lose them. We will fly you to Halle tomorrow."

We went by bus from Leipzig to Halle that afternoon, and flew out of Halle in a DC3 next morning, and landed in Reims, France. After being deloused again, we boarded a Lancaster near Reims, and flew over the old battlefields of the Somme with the old trenches still visible. It was a pleasant sight to see the Cliffs of Dover and the grand old England on or about the 11/5/1945. The British people were very good to us, the W.A.A. F's even gave their milk ration up to help get the Ex POW's on the road to good health after restricted diet of POW life.

We left England in the ship Orion, on 8/8/1945 from Liverpool via Panama, Wellington in New Zealand, arriving in Sydney on 9/9/1945. I was very grateful to come home after three years overseas.

Now, fifty years old in good condition, my rug is a target for the National War Memorial to preserve for future generations to look at. If I let the Memorial have it, I must sign an agreement giving them full ownership of the rug. Government with their mad ideas to sell or privatise everything we own, brings to notice 'Can they be trusted?' The memorial people are good and honest, but so-called do-gooders when in government become a problem.

This rug measures approximately 6'1" X 6'4" and weighs eleven and one fifth pounds.

Written by J.O. Simpson on 10/12/1995

+++

The Man from Snowy River

by Andrew Barton 'Banjo' Paterson

THERE was movement at the station, for the word had passed around

That the colt from old Regret had got away,

And had joined the wild bush horses - he was worth a thousand pound,

So all the cracks had gathered to the fray.

All the tried and noted riders from the stations near and far

Had mustered at the homestead overnight,

For the bushmen love hard riding where the wild bush horses are,

And the stock-horse snuffs the battle with delight.

There was Harrison, who made his pile when Pardon won the cup,

The old man with his hair as white as snow;

But few could ride beside him when his blood was fairly up-

He would go wherever horse and man could go.

And Clancy of the Overflow came down to lend a hand,

No better horseman ever held the reins;

For never horse could throw him while the saddle-girths would stand,

He learnt to ride while droving on the plains.

And one was there, a stripling on a small and weedy beast,

He was something like a racehorse undersized,

With a touch of Timor pony-three parts thoroughbred at least-

And such as are by mountain horsemen prized.

He was hard and tough and wiry-just the sort that won't say die-

There was courage in his quick impatient tread;

And he bore the badge of gameness in his bright and fiery eye,

And the proud and lofty carriage of his head.

But still so slight and weedy, one would doubt his power to stay,

And the old man said, "That horse will never do

For a long and tiring gallop-lad, you'd better stop away,

Those hills are far too rough for such as you."

So he waited sad and wistful-only Clancy stood his friend -

"I think we ought to let him come," he said;

"I warrant he'll be with us when he's wanted at the end,

For both his horse and he are mountain bred.

"He hails from Snowy River, up by Kosciusko's side,

Where the hills are twice as steep and twice as rough,

Where a horse's hoofs strike firelight from the flint stones every stride,

The man that holds his own is good enough.

And the Snowy River riders on the mountains make their home,

Where the river runs those giant hills between;

I have seen full many horsemen since I first commenced to roam,

But nowhere yet such horsemen have I seen."

So he went - they found the horses by the big mimosa clump -

They raced away towards the mountain's brow,

And the old man gave his orders, 'Boys, go at them from the jump,

No use to try for fancy riding now.

And, Clancy, you must wheel them, try and wheel them to the right.

Ride boldly, lad, and never fear the spills,

For never yet was rider that could keep the mob in sight,

If once they gain the shelter of those hills.'

So Clancy rode to wheel them-he was racing on the wing

Where the best and boldest riders take their place,

And he raced his stock-horse past them, and he made the ranges ring

With the stockwhip, as he met them face to face.

Then they halted for a moment, while he swung the dreaded lash,

But they saw their well-loved mountain full in view,

And they charged beneath the stockwhip with a sharp and sudden dash,

And off into the mountain scrub they flew.

Then fast the horsemen followed, where the gorges deep and black

Resounded to the thunder of their tread,

And the stockwhips woke the echoes, and they fiercely answered back

From cliffs and crags that beetled overhead.

And upward, ever upward, the wild horses held their way,

Where mountain ash and kurrajong grew wide;

And the old man muttered fiercely, "We may bid the mob good day,

No man can hold them down the other side."

When they reached the mountain's summit, even Clancy took a pull,

It well might make the boldest hold their breath,

The wild hop scrub grew thickly, and the hidden ground was full

Of wombat holes, and any slip was death.

But the man from Snowy River let the pony have his head,

And he swung his stockwhip round and gave a cheer,

And he raced him down the mountain like a torrent down its bed,

While the others stood and watched in very fear.

He sent the flint stones flying, but the pony kept his feet,

He cleared the fallen timber in his stride,

And the man from Snowy River never shifted in his seat-

It was grand to see that mountain horseman ride.

Through the stringy barks and saplings, on the rough and broken ground,

Down the hillside at a racing pace he went;

And he never drew the bridle till he landed safe and sound,

At the bottom of that terrible descent.

He was right among the horses as they climbed the further hill,

And the watchers on the mountain standing mute,

Saw him ply the stockwhip fiercely, he was right among them still,

As he raced across the clearing in pursuit.

Then they lost him for a moment, where two mountain gullies met

In the ranges, but a final glimpse reveals

On a dim and distant hillside the wild horses racing yet,

With the man from Snowy River at their heels.

And he ran them single-handed till their sides were white with foam.

He followed like a bloodhound on their track,

Till they halted cowed and beaten, then he turned their heads for home,

And alone and unassisted brought them back.

But his hardy mountain pony he could scarcely raise a trot,

He was blood from hip to shoulder from the spur;

But his pluck was still undaunted, and his courage fiery hot,

For never yet was mountain horse a cur.

And down by Kosciusko, where the pine-clad ridges raise

Their torn and rugged battlements on high,

Where the air is clear as crystal, and the white stars fairly blaze

At midnight in the cold and frosty sky,

And where around the Overflow the reedbeds sweep and sway

To the breezes, and the rolling plains are wide,

The man from Snowy River is a household word to-day,

And the stockmen tell the story of his ride.

+++

Australia's First Folk Festival

The late Con Klippel was passionate about music and family tradition. Con also loved the Upper Murray, crisp mountain air and socializing with friends through good music, song and dance.

Keith Klippel with The Festival Founder, Conrad A. Klippel

He was a good mate of the late Tom Mitchell and lived in the Nariel Valley all his life. Here Con raised 3 children with his wife, Beat.

Con and Beat married in 1931 and together they milled there own timber and built their own home, making many of the household furnishings. Con was the musician and Beat a great hostess and old time dancer, teaching many of the locals. Both were highly resourceful people but most of all, they loved good company and a laugh.

Con knew the Nariel Valley like the back of his hand. He knew every rock and trout pool, grew fantastic vegetables and fruits for preserves. He also had an appreciation for the indigenous people, their cultural sites and story telling. He loved developing friendships through music and was very passionate about his life. He was known to recite poetry and verse in his sleep.

In the early 1960s, Con hosted a couple from Melbourne who were interested in collecting music. Con and Beat were "discovered" when the city folk stopped at Omeo and were told to drive on over the Gibb to meet the Klippels at Nariel. Con and Beat's fine country hospitality obviously paid off. They organized family and friends to attend a special dance for the Melbourne visitors. They played music and danced until the early hours of the morning. The night was a huge success so Con decided to initiate Australia's first Folk Festival in 1963 and keep a good thing going.

The Nariel Creek Black and White Old Time Dance Band: Syd Simpson, Charlie Farden, Betty Coulston, Conrad "Keith" Klippel, Neville Simpson, Conrad "Con" Klippel and George Klippel.

Con soon became known for his "Nariel style" music, yet his accordion playing was an inherited talent from his grandfather who migrated from Germany in 1851.

The music collectors of the early 60s inspired Con to do his bit to preserve and protect his heritage too. Con started to write frantically to friends and family throughout Australia to promote his dream and vision, a festival that embraced all cultures and music styles. Con wanted all people to celebrate their heritage and share their stories through music, dance and song.

In the early 70s thousands of people gathered and the ABC made a special documentary about the unique Black and White Folk Festival. Con's mates would play the Gum Leaf and the Swaggy would tell his tale. There were violins, tin whistles, banjos and didgeridoos. The crowds loved it, it made national headlines and the setting was superb! Campers then followed from all over Australia to enjoy a week of music and good entertainment along the banks of the Nariel Creek every Christmas New Year. During the day music and cultural differences were embraced but when night fell, it was reserved for Con's Old Time Black and White Dance Band.

Con also developed a junior dance band to learn the traditional music, dance and song. He wanted to leave a legacy and today some of the original junior dance band members still play their accordions and gather at the Christmas New Year celebration, established in 1963.

The original Black and White Old Time dance Band incorporated Con's cousins, brother and son Keith. Keith, 69, still plays for the festival. Today it's called the Nariel Creek Folk festival, the essence of friendships and cultural exchange through music still remains. It is a historic site where people have been playing music and celebrating for thousands of years.

Con's motto was "My greatest joy in life is making people happy".

Con died performing on stage in 1975 aged 66. His family photos, story and many family artifacts can been seen at the Man from Snowy River